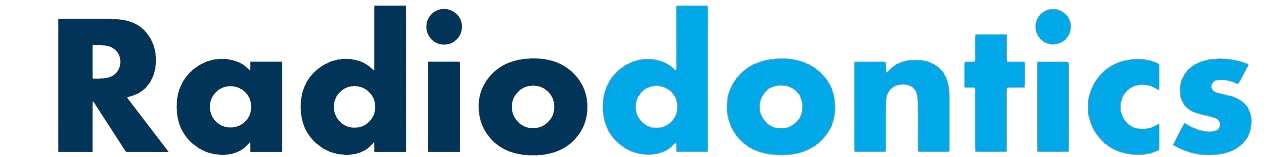

Panoramic Radiopacities

Dr. Barett Andreasen, Oral and Maxillofacial Radiologist

Radiopacities on a panoramic radiograph occur relatively infrequently but when they do appear, superimposition of anatomical structures and the inherent 2D nature of panoramic imaging makes localization and diagnosis of these radiopacities challenging. A proper understanding of the common radiopacities found on panoramic radiographs is critical to ensure appropriate management of patients.

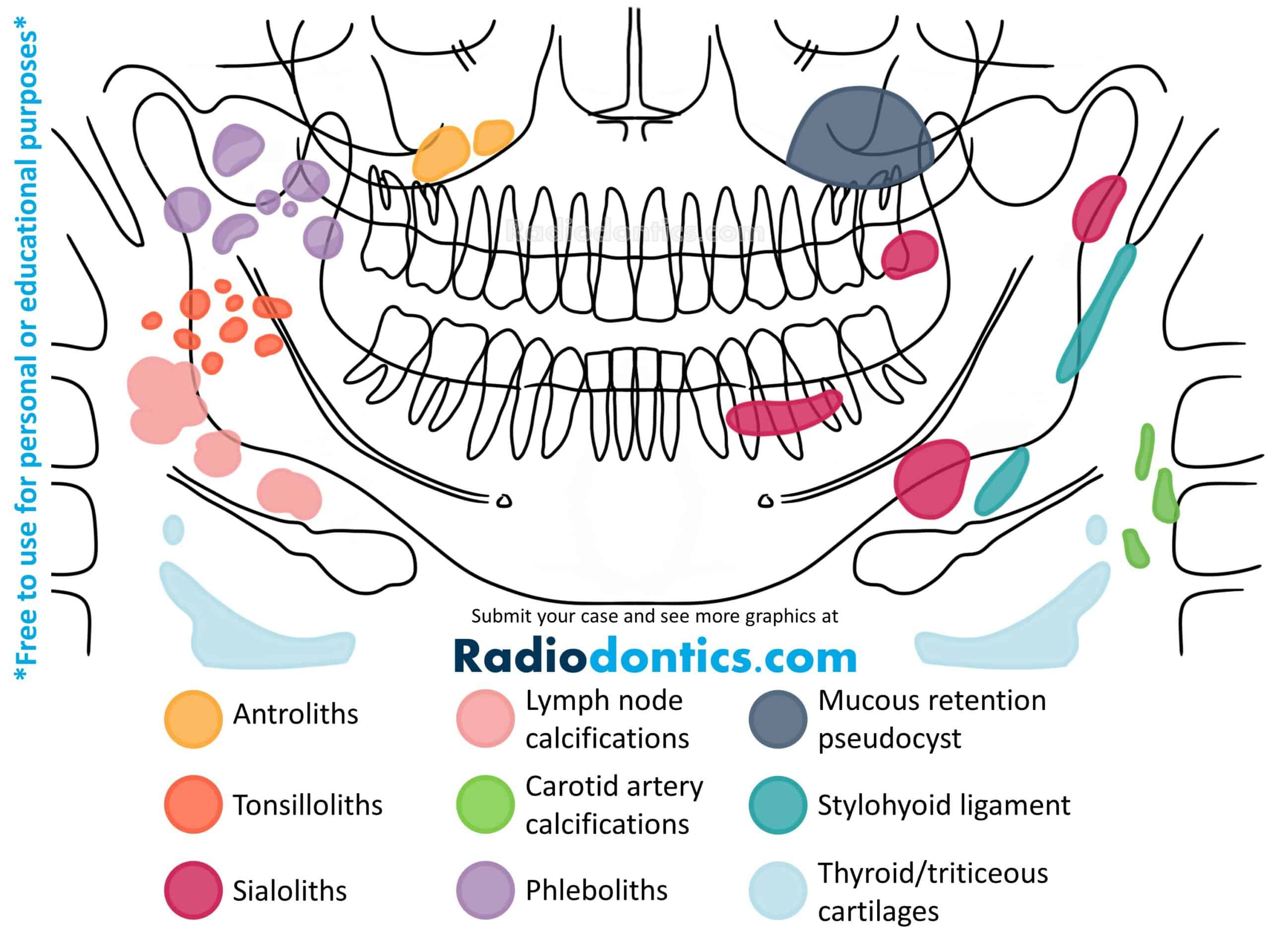

Antroliths

Antroliths appear as a calcified mass within the maxillary sinus separated from the adjacent sinus floor. Antroliths are often formed in the environment of chronic sinusitis and may originally calcify from a nidus of inflamed mucus, pus, clots or foreign bodies.

Antroliths present as a well-defined calcified mass, ranging from a faint to dense radiopacity with a laminated appearance. They are roughly spherical or ovoid in shape and may be solitary or multiple in number. Antroliths may also appear in periapical radiographs of the posterior maxillary teeth.

No treatment for the antroliths themselves is necessary, if asymptomatic. However, the underlying cause for possible chronic sinusitis may need to be addressed. Treatment for chronic sinusitis can range from simple antibiotics to sinus surgery. Fungal sinusitis (aspergillosis) should be considered in cases that are unresponsive to therapy.

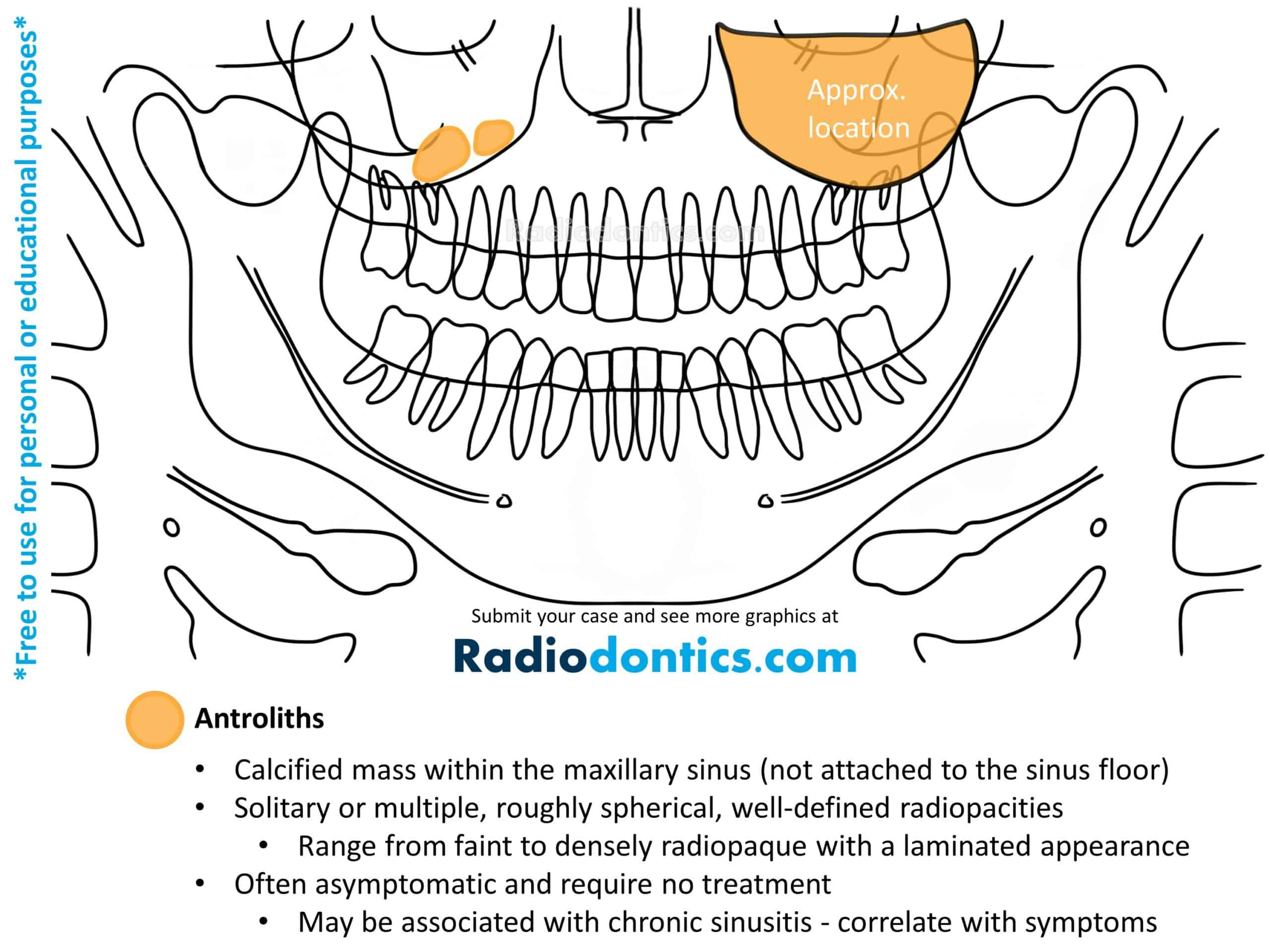

Tonsilloliths

Tonsilloliths (tonsil stones) are clusters of calcifications that arise in the tonsillar crypts of the palatine tonsils. These dystrophic calcifications are formed secondary to condensed necrotic debris and bacteria and can be found in a wide population, although they are more common in older age groups.

Tonsilloliths appear as single or multiple small, round or irregularly shaped radiopacities. On panoramic radiographs, they are typically found superimposed over the mid-ramus or located just posterior and inferior to the mandible in the region of the dorsal surface of the tongue. Tonsilloliths may be unilateral or bilateral.

No intervention is required if the patient is asymptomatic. However, tonsilloliths can promote recurrent tonsillar infections and may lead to soreness, dysphagia, halitosis, or other symptoms. In these cases, patients may attempt removal by gargling warm salt water, though curettage or local excision may be required if home treatment is unsuccessful.

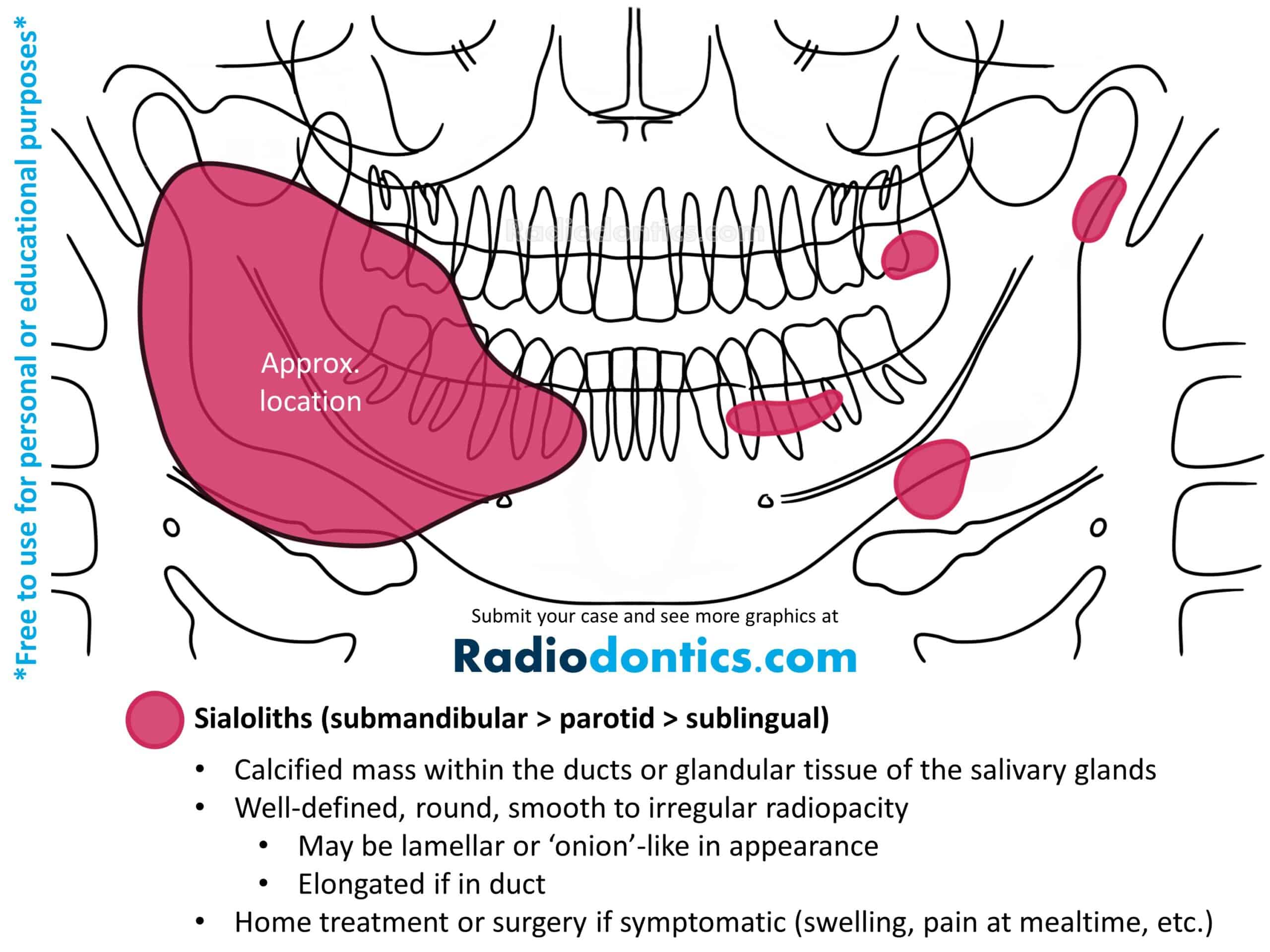

Sialoliths

Formation of a mineralized mass within the salivary glands or ducts is termed a sialolith (salivary stone). Sialoliths arise from calcium deposits that form around a nidus within the duct lumen. Of the major salivary glands, the submandibular gland is most often involved, likely due to the upward and tortuous nature of the submandibular duct as well as its thicker, mucoid secretions.

On panoramic radiographs, sialoliths present as a well-defined radiopacity that ranges from completely radiopaque to mixed-density in appearance. A lamellar or 'onion'-like appearance may be evident, reflecting the chronic and repeated deposition of calcium that forms these entities. Sialoliths are normally spherical or oval with smooth borders, but can be elongated if within a duct. Solitary sialoliths are seen most frequently; however, multiple stones may be seen involving the parotid gland and can mimic calcified lymph nodes (such as might occur in tuberculosis).

Patients may present with a history of recurrent swelling and/or pain during mealtimes, though many cases are asymptomatic. Stimulation of salivary flow, hydration, massage and moist heat can often dislodge smaller sialoliths. Larger stones may require surgical intervention, such as excision or sialoendoscopy.

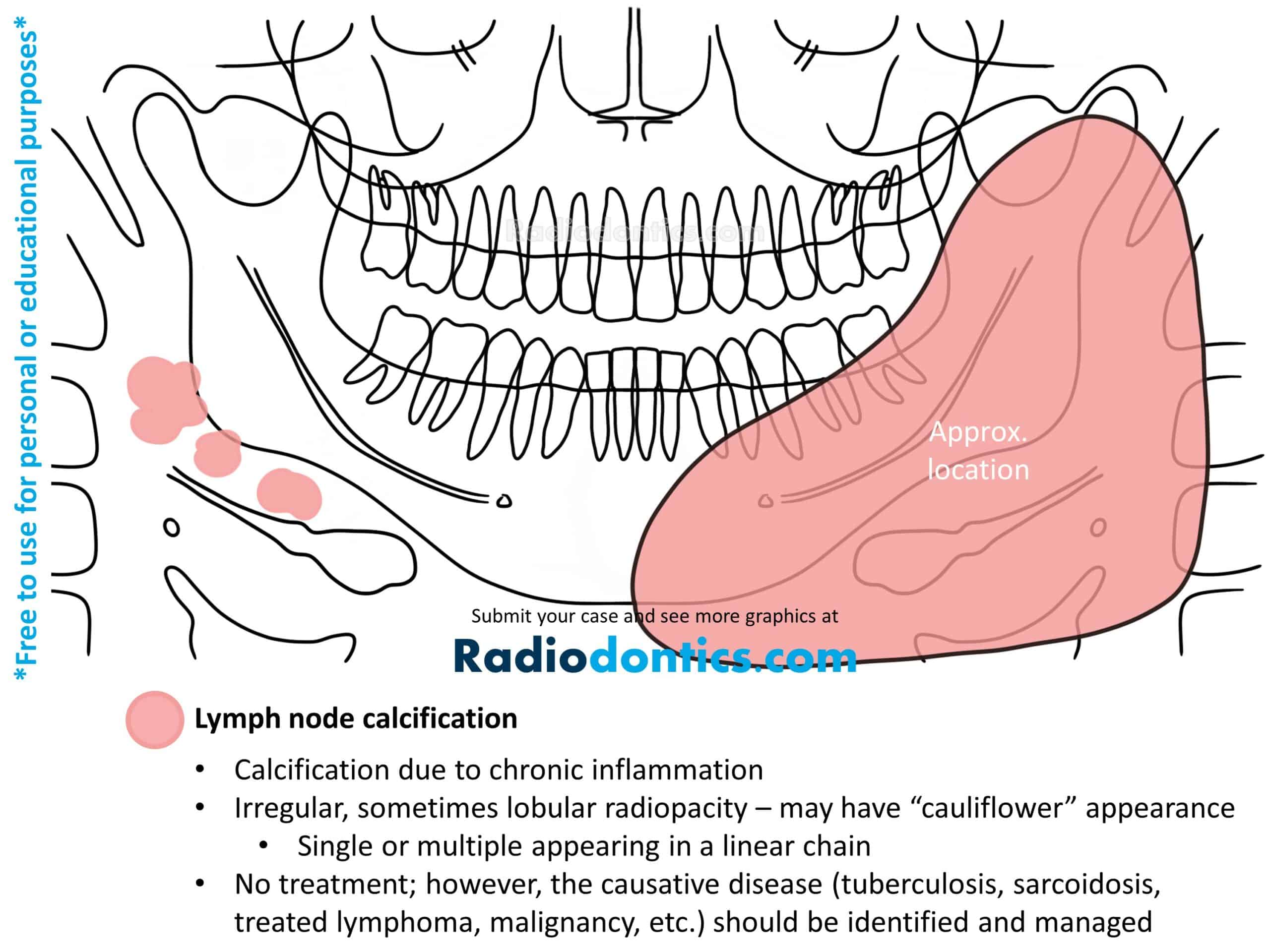

Lymph Node Calcifications

Calcification of lymph nodes results from chronic inflammation, either caused by a prior or active disease process. Calcified lymph nodes are most commonly seen in patients with tuberculosis, fungal infections, sarcoidosis, systemic sclerosis, lymphoma treated with radiation therapy, and malignancies (such as metastatic thyroid carcinoma).

Lymph node calcifications appear as radiopacities with well-defined and irregular borders. Most often the shape is described as having a lobulated or cauliflower appearance with the internal structure demonstrating a varying degrees of radiopacity. Other times, the presentation is more lamellar, making it difficult to distinguish them from sialoliths. The calcifications may involve a single node or a linear series of nodes, known as "chaining."

Calcified lymph nodes are usually found at or near the inferior and posterior borders of the mandible and may be superimposed over the mandible itself.

No treatment is indicated, as calcified lymph nodes are usually asymptomatic. However, the causative disease should be identified with a thorough review of the patient's medical history to rule out an active disease process.

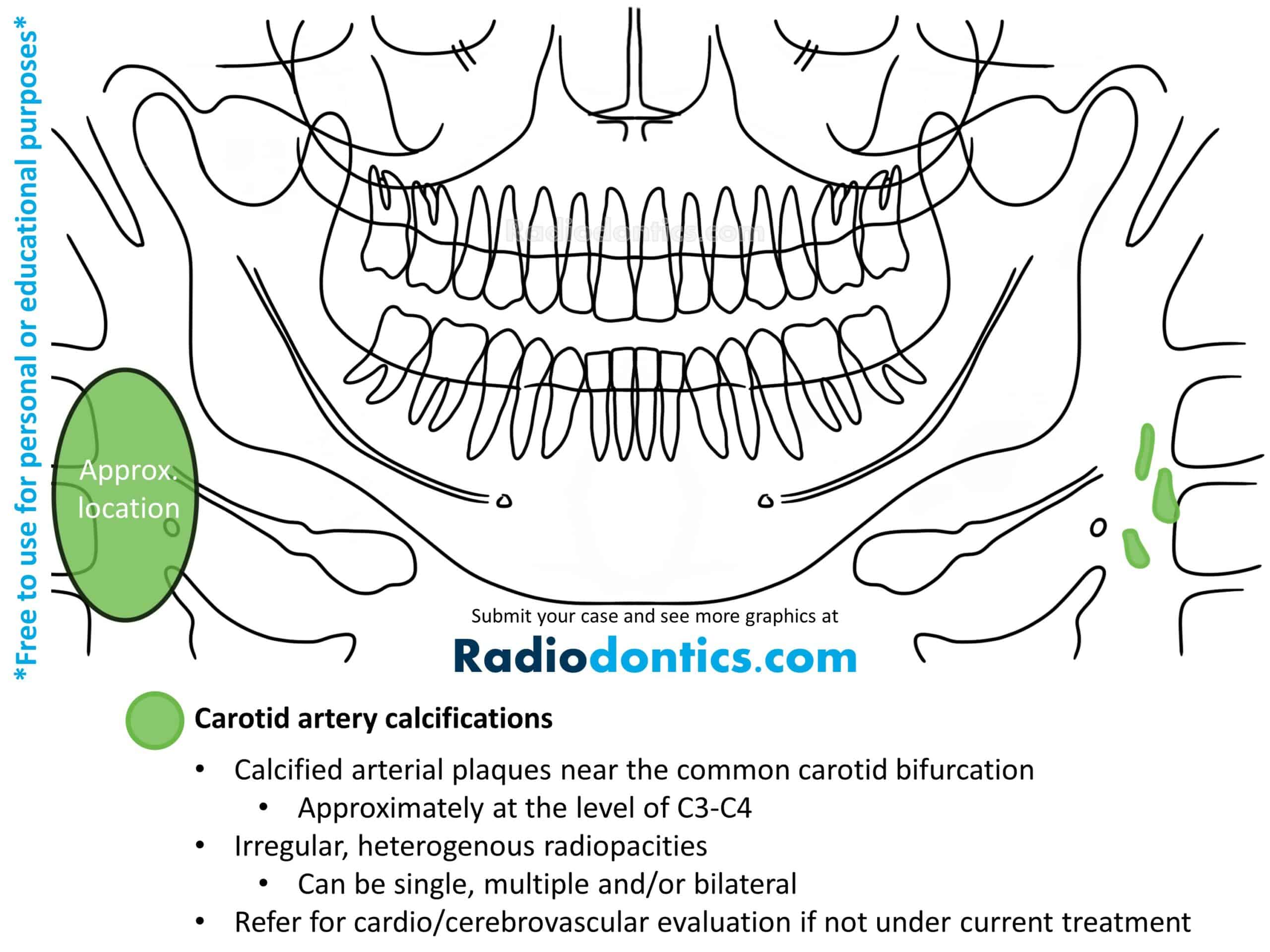

Carotid Artery Calcifications

Atherosclerosis is characterized by the deposition of carotid artery plaques along the inner walls of the arteries. During the evolution of these plaques, dystrophic calcifications may develop which can be observed in panoramic radiographs.

Carotid artery calcifications usually appear as irregular, heterogenous radiopacities. They can be single or multiple and demonstrate a vertical linear distribution. Carotid artery calcifications are observed in the area of the carotid artery bifurcation, which is located adjacent to the third and fourth cervical vertebrae and near the greater cornu of the hyoid bone.

Carotid artery calcifications be mistaken for triticeous and thyroid cartilage calcifications. Triticeous and thyroid cartilage calcifications demonstrate a more uniform size, shape and location, which helps distinguish them from carotid artery calcifications.

If not currently being treated, patients with carotid artery calcifications should be referred to their physician for further cardiovascular and cerebrovascular examination as early identification and medical intervention reduces the risk of vascular events.

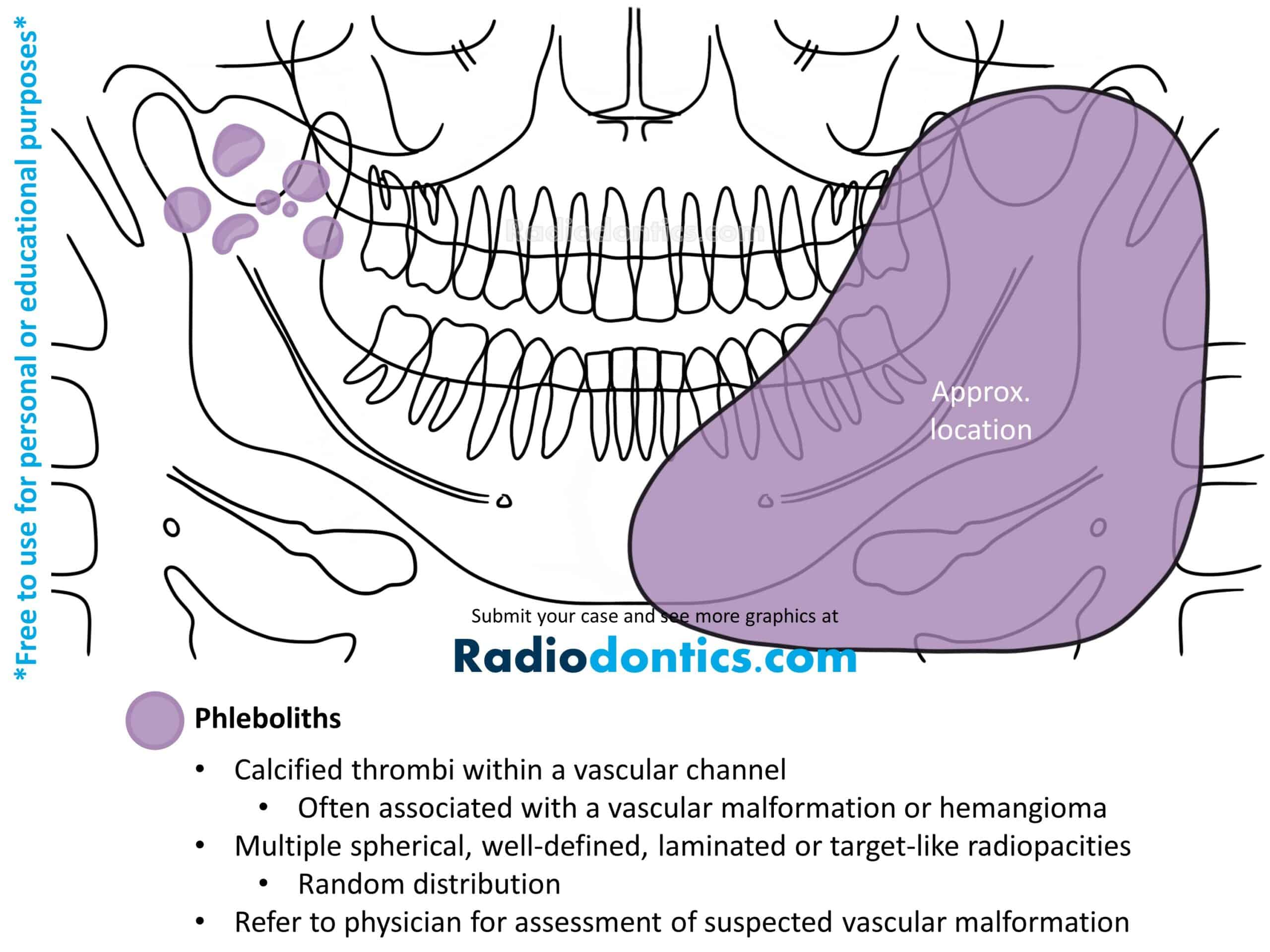

Phleboliths

Phleboliths (vein stones) are calcified thrombi most often associated with vascular malformations or hemangiomas. They form due to stagnation or disruption of normal blood flow within a vessel which causes the mineralization of a thrombi into a calcified mass.

Phleboliths are round or oval in shape with a smooth periphery and will often demonstrate a 'target-like' or laminated appearance, consisting of alternating layers of radiolucency and radiopacity. Multiple phleboliths in a random distribution is a common finding.

As phleboliths usually accompany vascular malformations, patients with phleboliths identified on their radiographs should be referred to their physicians for further assessment (if patient hasn't already received treatment). Proper management of vascular malformations is needed as lesions can undergo periods of rapid growth with infiltration and destruction of adjacent tissues. Vascular malformations also pose a risk of severe and even fatal hemorrhage, which may occur spontaneously or during surgical manipulation, such as during incisional biopsies or extractions of adjacent teeth.

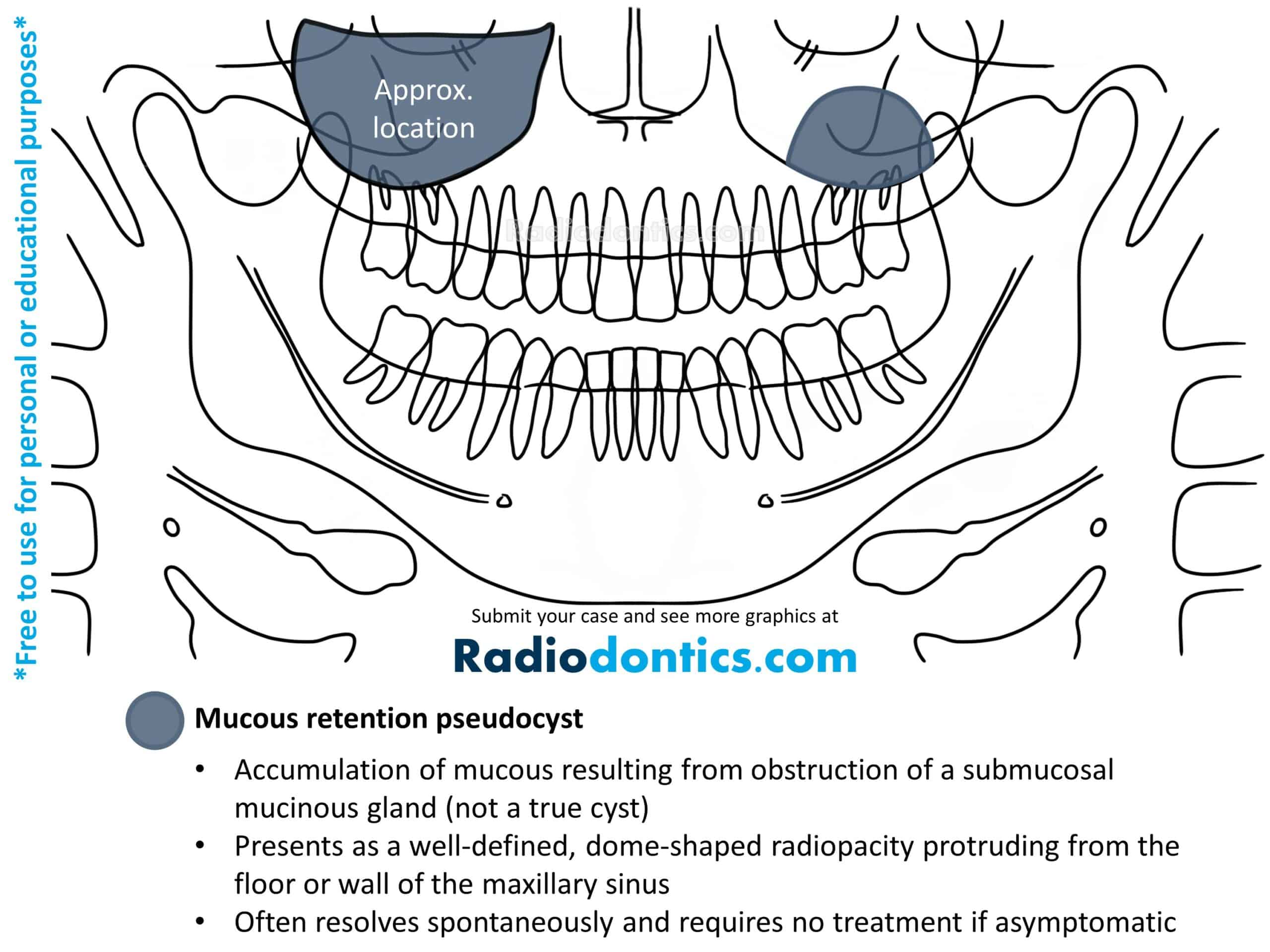

Mucous Retention Pseudocyst

Mucous retention pseudocysts occur when submucosal mucinous glands within the paranasal sinuses become obstructed. This leads to an accumulation of fluid beneath the sinus mucosa and results in a swelling of the tissue.

The radiographic appearance of mucous retention pseudocysts is described as a dome-shaped radiopacity along the floor or wall of a sinus. The borders are well-defined and smooth but lack cortication. Mucous retention pseudocysts have no effect on the surrounding structures and as such, the borders of the involved sinus should always remain intact and without any expansion or displacement. If the pseudocyst is superimposed over the roots of a tooth, the lamina dura and PDL space should be unaffected. Mucous retention pseudocysts may also be evident on maxillary posterior periapical radiographs.

No treatment is typically necessary for mucous retention pseudocysts as they normally cause no symptoms and resolve spontaneously without any surgical intervention.

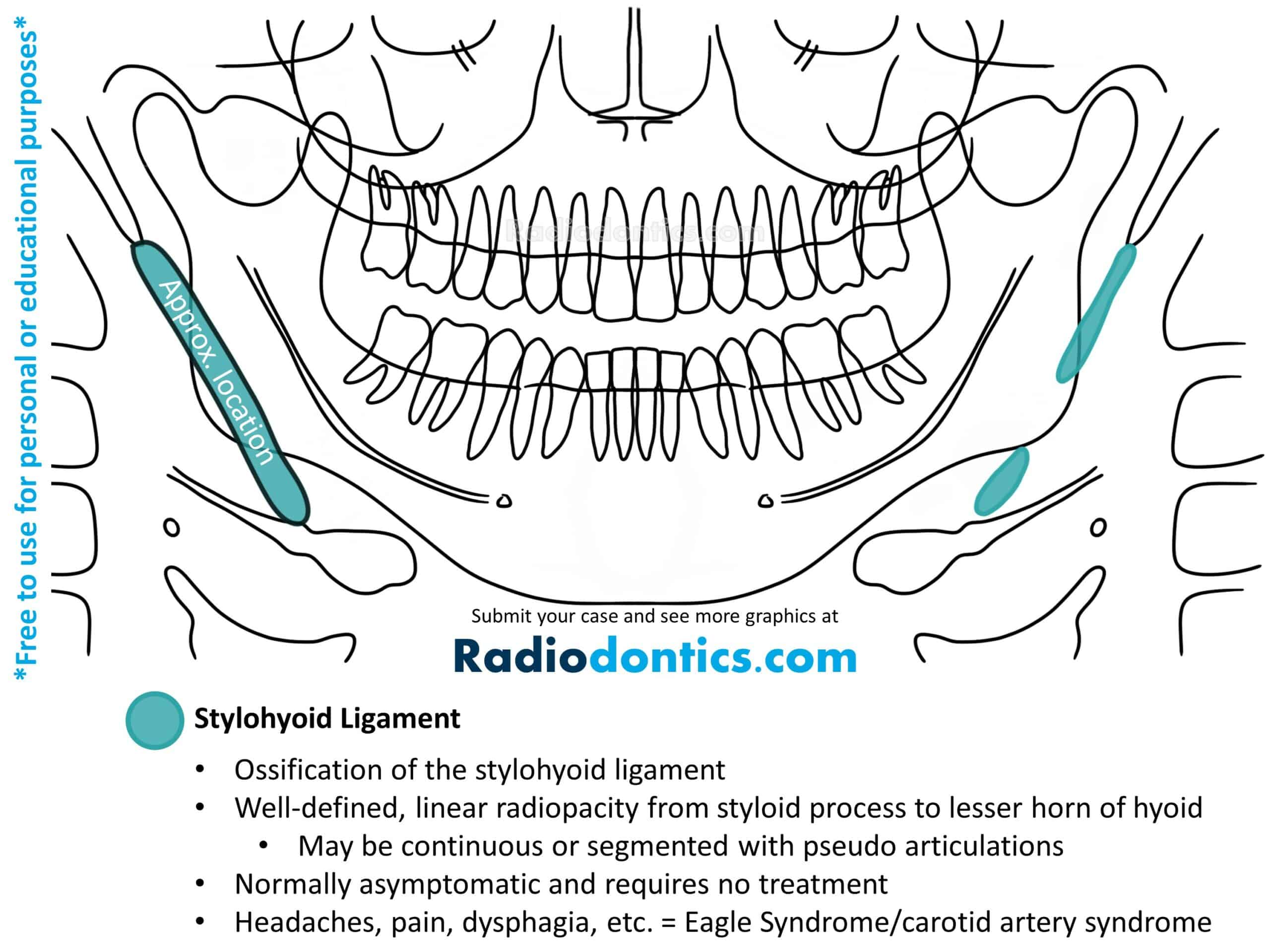

Stylohyoid Ligament

The stylohyoid ligament is a fibrous band that runs from the styloid process of the temporal bone and inserts into the lesser horn of the hyoid bone. Ossification of this ligament can occur and is a common incidental finding in panoramic radiographs.

Small ossifications of the stylohyoid ligament present as a uniform, linear radiopacity with larger ossifications usually demonstrating a denser, more radiopaque periphery with a less radiopaque internal structure. The ossification is normally seen as an elongation of the stylohyoid process; however, it may instead originate from the lesser horn of the hyoid bone or can even begin in a central area of the ligament. Borders are typically smooth and straight, but in some cases surface irregularity may be seen. More extensive ossifications can demonstrate segmentations or pseudoarticulations.

The vast majority of patients with ossification of the stylohyoid ligament are asymptomatic and require no treatment. When symptoms such as headaches, pain while swallowing, turning the head or opening the mouth, dysphagia, visual disturbances, or foreign body sensation in the pharynx are present, Eagle syndrome and carotid artery syndrome should be considered. Eagle syndrome is reserved for symptoms related to a recent history of neck trauma (typically tonsillectomy) while carotid artery syndrome is preferred when the above clinical findings are present without a history of neck trauma. The severity of symptoms is often unrelated to the degree of ossification present.

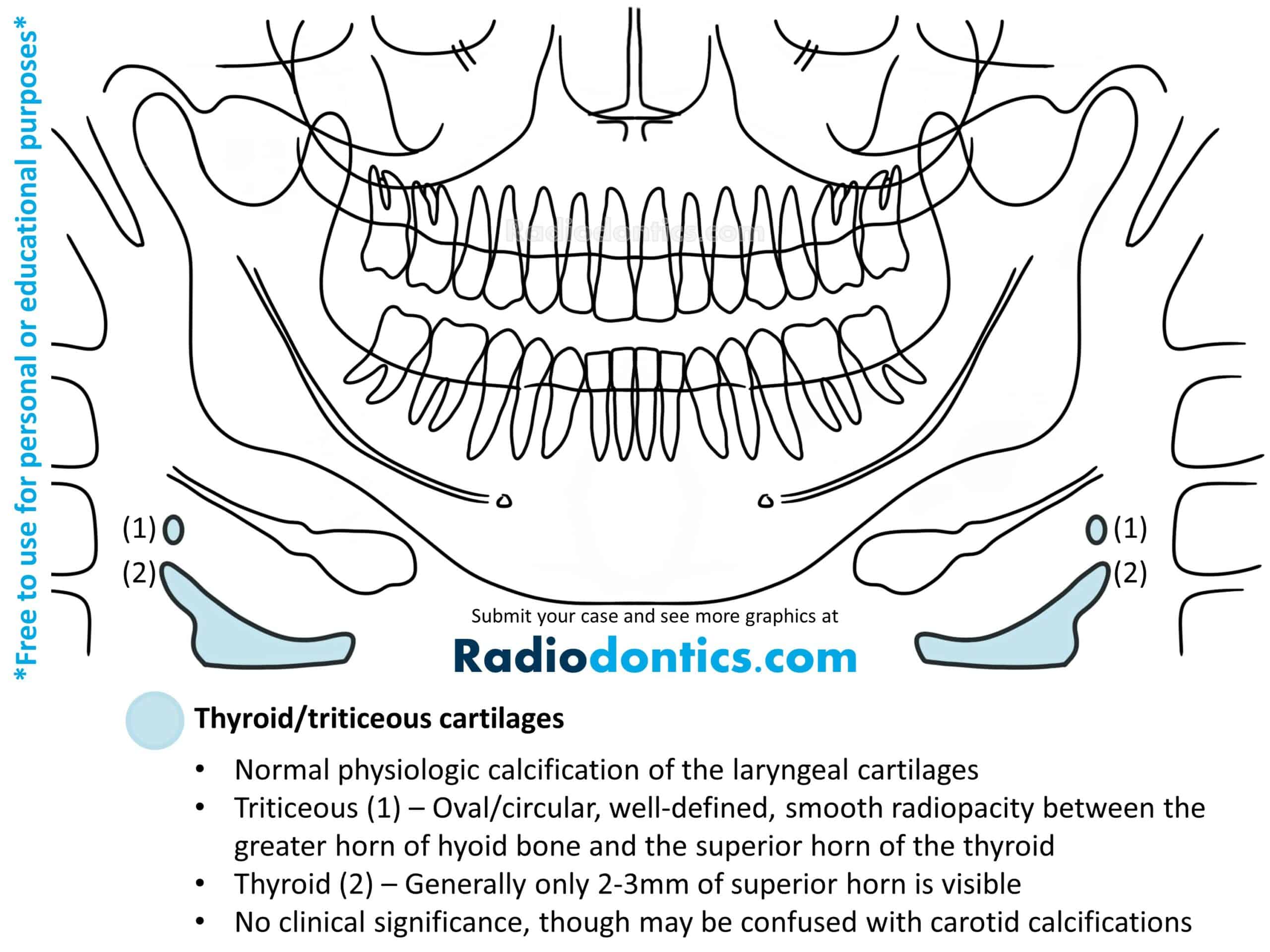

Thyroid/Triticeous Cartilages

Beginning at skeletal maturity, the hyaline laryngeal cartilages (the thyroid, triticeous, cricoid and arytenoid cartilages) undergo endochondral calcification and ossification. This process is a normal physiological change and continues throughout the patient's life. Occasionally, the calcification of the thyroid and triticeous cartilages can be seen on panoramic radiographs.

The triticeous cartilages present as paired small, well-defined, smooth, round or ovoid radiopacities inferior to the greater horn of the hyoid bone and superior to the superior horn of the thyroid. Calcified triticeous cartilages often are homogenously radiopaque but depending on the degree of calcification may demonstrate a identifiable peripheral cortex.

The superior horn of the thyroid cartilage can also be evident on panoramic radiographs, appearing medial to the C4 vertebra. The appearance varies with the degree of calcification, ranging from a faint incomplete outline to a distinct corticated border with a less dense internal structure.

As these are normal physiological changes, no treatment is needed for calcified thyroid and triticeous cartilages. Careful examination is advised to distinguish between calcified laryngeal cartilages and carotid artery calcifications.

A Word of Caution

There are, as always, exceptions to these rules. As anyone who practices in the field of dentistry knows, nothing ever quite follows the textbooks, especially when delving into the field of pathology and radiology. The entities covered above demonstrate many various presentations and manifestations which cannot be covered in this article, and that's not to mention the numerous pathologies which were not discussed.

If you have any questions about a radiograph, please click on the 'Upload Case' button below to have your images be reviewed by an oral and maxillofacial radiologist.